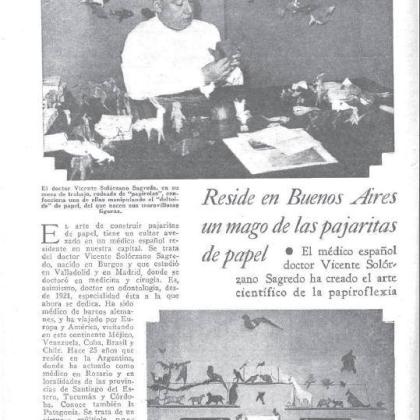

Vicente Solorzano Sagredo

Burgos

Spain

Life and works

Vicente Solórzano Sagredo was born in Spain, in Burgos, on July 24, 1883, son of humble parents. Already in his early years, his mother taught him to fold some traditional figures, pajaritas, boats, frogs, and whales. He folded them all the time and distributed his creations at school to all the children and, according to the story, secretly from the teachers. When he grew up he often referred to the influence that his mother has had on his hobby, who, with 'her sweet hands, folded hats and bishop's mitres that she put on her blond head to adorn it'.

When he was 12 years old, his mother died, a fact that marked him for the rest of his life. He moved with his father shortly after to Valladolid where Vicente continued his studies and finally entered the university.

He takes advantage of medicine, literature, mathematics, and anatomy classes to fold all kinds of models: dogs, monkeys, and cows, which he continues to distribute among his classmates. Everyone's admiration for his great manual skills grew.

At the university Solórzano also became fond of music, especially the violin. With the tuna of students, he travels around towns with his friends and never stops folding and folding.

At the age of 23, Vincente also loses his father, a new blow to his morale. The memory of his parents will always be present in his life, dedicating all his books to them.

Solórzano finished college with a degree in medicine and received his doctorate in Madrid. He joined the Merchant Navy as a doctor and began a journey of several years traveling on ships of all types and numerous shipping companies. He traveled half the world, especially South America and Europe for four years. The violin and paper models were his most faithful companions during this period.

The year was 1911 and, to put the historical perspective, another great character of origami, Akira Yoshizawa, was born that year in Japan.

Dr. Vicente Solórzano took up residence in Argentina, in Buenos Aires, where he gradually specialized in dentistry and was able to demonstrate his great manual skills. He spent the following years learning English, playing the violin, the piano, and, of course, folding and designing ’pajaritas’.

In 1928, when he was already 45 years old, he exhibited his first origami Nativity in Buenos Aires.

In 1935, when he was already 52 years old, came the great change, and the growth of his figure as a creator and origamist. According to his story, while living on the beautiful beaches of Necochea, more than 500 km south of Buenos Aires, one afternoon, he spotted some penguins on the coast. That fortunate observation inspired him to design new ’pajaritas’. His hands created more than 50 variations.

The idea of publishing a book that collected all these models began to haunt his mind. He began to explore the almost non-existent bibliography that existed on the subject and the book ’Amor y Pedagogía’ ('Love and Pedagogy’) by the Spanish writer and philosopher Miguel de Unamuno fell into his hands. In the book's appendix, 'Apuntes para un tratado de Cocotología' (’Notes for a Treatise on Cocotology’), Solórzano discovers a treasure trove of origami. He says, not so much for its pedagogical or scientific value for folding, which is what he had been developing, but for its philosophical values and thinking about folding. If Unamuno folded almost by intuition, he tries to develop a methodology of folding, applying mathematics to discover the science that lies beneath the paper models.

He moved to Buenos Aires with the firm intention of publishing an origami book and dedicating it to Unamuno. He could not fulfill his wish because the latter died a year after. The publication finally came in 1938, PAPIROLAS I, the first of a series of three. With this book, he made himself known to origami enthusiasts, one of them being the famous Argentinian Ligia Montoya, who was a disciple and collaborator of Solórzano in later works. The disciple grew and in many aspects surpassed the master, becoming in turn a great master. But that is another story.

By then Solórzano had made numerous exhibitions in Argentina and had already published several books. In these first publications Solórzano 'founded' a new science, Papiroflexia, as he would call it.

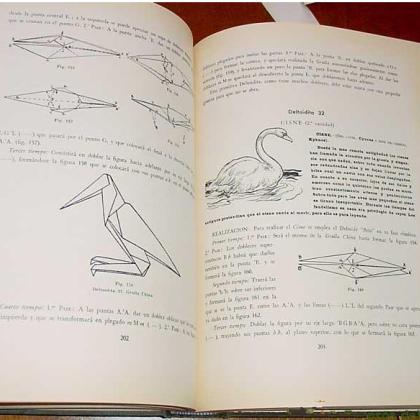

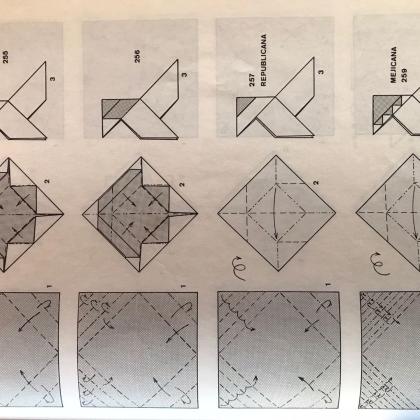

In 1944, when he was 61 years old, he published his 'Tratado de Papiroflexia Superior', where numerous mathematical references and geometrical figures appear, which he called deltoids. The deltoids were for Solórzano the primordial constructive blocks that gave rise to the rest of the origami figures. These deltoids were the traditional bases and their derivatives. In later publications, he would develop and classify them by types.

The deltoids, at least some of them, were already known in the West by Unamuno and his disciples and in the East as the basis of traditional folds, especially the crane. But it is true that Solórzano developed them, classified them in his way, and created countless figures from them.

Dr. Solórzano collected and classified the basic folds, mainly by their number of flaps and their length and proportion. In this way, if he wished to create a model of a certain animal, he would begin by choosing a base that had the necessary flaps, and then use his ingenuity to get as close as possible to the intended shape.

In those pioneering times, origami was developing and techniques such as using cuts were not uncommon in the models. When Solórzano referred to Unamuno's works, as very schematic, he said that being simple, they did not require more than folding, however, the scientific art of origami goes further trying to get more and more anatomically perfect models. In these cases, small cuts in the folded paper would help to achieve better models. Many of his creations have such cuts. He himself wonders if these same models could be made without cuts.

Other publications followed in 1947, such as the six 'Papirolas Escolares' primers.

In 1954, Dr. Vicente Solórzano founded what could be the first origami museum in the world, in Buenos Aires. Throughout the years, many personalities passed through his house museum. At the same time, the numerous Japanese origamists immigrants in Argentina founded an academy for the teaching of origami. Solórzano's relationship with the Japanese was not very good because they refused to use the word 'papiroflexia' instead of 'origami'. Dr. Solórzano was a person who must have had a complex personality and had more than one problem with some of his fellow hobbyists.

The word 'Papiroflexia', as well as 'Papirolas', owe their origin to Solórzano who began to use and promote them in his books. Eventually, they ended up being accepted by the Real Academia de La Lengua Española and are the synonym of the more international term 'origami'.

Perhaps Solórzano's best supporter was his friend and great origamist, Dr. Nemesio Montero. They were both medical students in Valladolid. Montero was Solórzano's "official representative in Spain" while he was living in Argentina. Solórzano tried to create an origami association in Spain back in the 1950s. There was even a news item published that reads:

Madrid, March 21, 1949

Having been founded in Buenos Aires (Argentina Republic) the Universal Society of Papirology and Papiroflexia, under the presidency of doctor Solórzano Sagredo has been constituted a Delegation of the same for Spain in Valladolid, where the fans to this interesting artistic and pedagogic specialty can send their adhesionaes, directed to doctor Montero, plaza del Campillo, number 3, being understood that by this inscription as associates, they are not obliged more than to the natural and voluntary relation with other associates whose list will be sent to them for the interchange of models and promotion of this hobby, having in mind to edit a magazine in which the new creations born of the artistic inspiration and ability of the associates will be collected.

The reality is that the Spanish association never became a reality until years after Solorzano’s death.

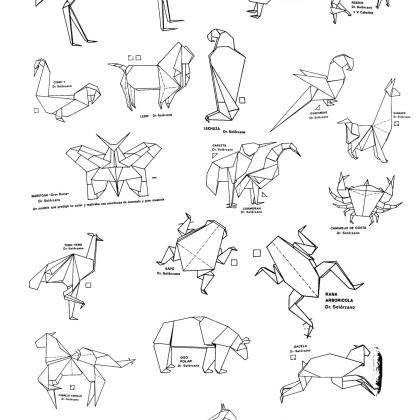

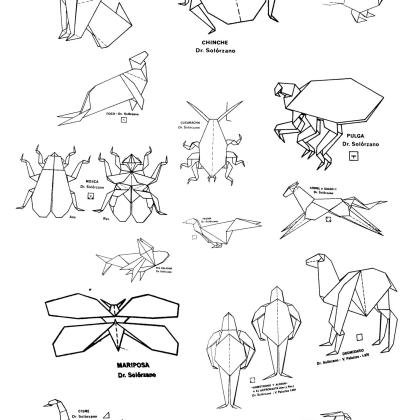

But before that, let's go through the most ambitious publication of his career. In 1962 'Papiroflexia Zoomorfica' finally appears as a monumental work with two books of 825 pages and 1716 drawings. It contains a total of 261 models.

The edition and publication were in charge of Solórzano himself who, according to his friend Nemesio Montero, was able to recover the total amount of the edition thanks to the sales. The aforementioned Ligia Montoya participated in the publication and helped to ink and improve hundreds of diagrams poorly drawn in pencil by Dr. Solórzano. Clearly, in this discipline, Ligia was much more skilled than the master. Ligia added numerous new diagrams and even improved some figures. Although Solórzano paid the agreed amount for Ligia's work in the publication he made no mention of Ligia, appropriating the diagrams and the improvements in some figures. The controversy was served and lasted for years. As the papiroflecta Vicete Palacios remembers, this was 'An unfortunate incident, fruit of the sad human condition, that ended only with the premature death of Ligia (by the year 1967) and of Dr. Solórzano (in 1970) close to reaching 87 years of age. Let us hope that they have finally made peace'.

Like all of Solórzano's works, 'Papiroflexia Zoomorfica' was not easy to understand. It used a whole terminology to describe the folds that made it almost incomprehensible to Spanish-speaking laymen and non-literates alike. If for Spanish speakers it was difficult to understand, for foreigners it would be almost impossible. The diagrams were designed to economize on drawings and were often complex to interpret. They were accompanied by cumbersome explanations with segments that had to be carried from one side to the other, making the reading complex. Nevertheless, these books were the ones that made a whole legion of folders and creators of the next generation of origami grow up. Unfortunately, Solórzano's books are nowadays very difficult to obtain and therefore, their reach to modern amateurs has been limited. Hence the relative lack of knowledge of his great work.

Don Vicente Solórzano Sagredo had a curious habit: he sent his publications as gifts to people of certain importance and, in this way, many were obliged to thank him by letter for the gift and they used to indicate how curious, surprising and artistic they found it.

Thus, in subsequent publications, Solórzano published the opinions that these prominent people had about his work. Renowned figures such as Miguel Delibes, Ramón Gómez de la Serna, Clara Campoamor or the Chilean poet Gabriela Mistral received Solórzano's works.

Vicente Solórzano died on March 9, 1970. His friend Nemesio Montero was named his executor, and in 1976 he was in charge of the transfer of his remains to Valladolid. Previously, in 1959, he was the custodian of the 2 trunks that kept the figures of the Museum that Solórzano opened in Buenos Aires and that today the Spanish Association of Origami enjoys as a deposit.

This article was written by Fernando Sanchez-Biezma, 2022