Primary tabs

Robert Harbin

london

london

United Kingdom

Summary

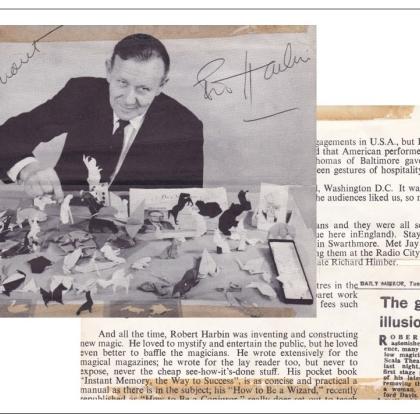

Edward Richard Charles Williams was born in South Africa in 1909 and died in London in 1978. He immigrated from South Africa to London in 1928 (or possibly 1929) and developed a successful career as a music hall, stage and television magician. At first, he performed as Ned Williams, but in 1932 he adopted the name Robert Harbin as both his professional name and nom de plume. In 1932 he married the dancer Edith Lilian Philp, who used the professional name of Dorothy Hall and was, for a while, his stage assistant.

Harbin was highly respected among magicians and was considered one of magic’s most brilliant creative geniuses, as well as a distinguished performer. He invented many ingenious tricks and illusions, among them the famous Zig-Zag Girl. Most were published in the weekly magic magazine ‘Abracadabra’ and in his magnum opus ‘The Magic of Robert Harbin’.

Like many other magicians before him, he became an enthusiastic paper folder. He invented many original designs of his own but his most significant contribution to the development of recreational and creative paper folding was made through his books and television appearances. It is probably no exaggeration to say that he introduced more people to origami than any other paperfolder since Friedrich Froebel, particularly in Great Britain. He also used his books to publicise the work of many of the best creative paperfolders of his time. Together with Lillian Oppenheimer and Gershon Legman, he has been credited as being one of the people most responsible for helping to forge closer links between paperfolders in Europe, South America, the USA, Japan and Australasia.

Contribution to the Development of Paper Folding

Childhood interest

In his introduction to his book ‘Paper Magic’ Harbin recorded that ‘At the age of 11 I made my first paper bird. From that moment my interest in paper-folding grew, due in the main to the fact that the making of these fascinating paper toys made me the centre of attraction in any family gathering.’

Two incidents in 1953

However, it seems that this boyhood interest in paperfolding did not completely blossom until early in 1953, when his wife unfortunately suffered severe burns in a dressing-room fire. While visiting her in hospital, Harbin came across some airmen who were folding paper as a form of occupational therapy, using Margaret Campbell’s book ‘Paper Toy Making’ as their exemplar. Although Campbell and Harbin were in fact distant cousins, it does not appear that Harbin had seen this book before. It made a big impression on him.

Around the same time, Harbin was contracted by the American film director Cy Endfield to appear as the character Harper LeStrade, a magician, in his film ‘The Limping Man’. Endfield was also interested in recreational paperfolding and, seeing Harbin folding paper during breaks in the filming, showed him how to fold a peacock from a bank note.

These two incidents reawakened Harbin’s interest in paperfolding and he started to collect as much information about paperfolding as he could, and to try to contact other people who were also interested in the subject. (By 1963 he was able to write about himself, in the third person, 'Origami has become his all-absorbing interest and his one pleasure is to be able to illustrate and explain his own creations and those of the many friends he has made through this fascinating hobby'.

In 1955 his hands appeared, folding paper, as ‘Mr Left and Mr Right’, in a short segment of the BBC children’s programme ‘Jigsaw’, which was shown on Saturday evenings. ‘Mr Left and Mr Right’ first aired on 2nd January 1955 and ran for six bi-weekly shows.

Contact with Gershon Legman

At some time during this period, probably quite early on, Harbin decided to try to write a definitive book about paperfolding. The information he was able to find was mostly about traditional Western European designs (although, when the book was eventually published, as ‘Paper Magic’ in 1956, it was also to contain a number of original designs by both Harbin himself, his illustrator Rolf Harris, and other paperfolders from around the world.) Information about Japanese paperfolding was much harder to come by and, in fact, Harbin came to believe that Japanese people no longer practised paperfolding.

In the Bibliography in ‘Paper Magic’ Harbin mentions that the book ‘Le Petits Secrets Amusants’, written by Alber-Graves, another magician, which was published in 1908, contained the information that ‘paper-folding ceased in Japan around 1889’. In fact this was a misunderstanding of the original French, which said ‘Aujourd’hui ce genre d’occupation est plus délaissé’ (nowadays this kind of occupation is more neglected in Japan).

In early 1955, when ‘Paper Magic’ was substantially complete, Endfield introduced Harbin to Gershon Legman, a boyhood friend of his, then living in the South of France, who had also been researching paperfolding for a number of years, and with much greater success. Legman was quickly able to correct Harbin’s impression that paperfolding had ceased in Japan and to introduce him to the work of Akira Yoshizawa, and of the Argentine paperfolders Vicente Solorzano and Ligia Montoya. While the main content of the book could not be altered at this late stage, Harbin was able to quote substantially from Legman’s letters, particularly the paragraphs about Yoshizawa, in his Introduction, and to add a much more substantial Bibliography to the work than would otherwise have been possible. These late additions made it a much better, and more influential, book.

The Oppenheimer Connection

Early in 1957 the American paperfolding enthusiast Lillian Oppenheimer received a copy of ‘Paper Magic’ as a gift from her son, Bill Kruskal. Oppenheimer immediately wrote to Harbin and subsequently arranged to meet him in London. She also went on to France to try to meet Legman, only to find that he was away from home. Nevertheless she began to correspond with Legman, and also with Yoshizawa and the other paperfolders whom Legman and Harbin had made contact with. This paved the way for the rapid growth and development of organised paperfolding in the USA.

Secrets of Origami

Harbin’s next major work was his book ‘Secrets of Origami’, published in early 1964. This was a very different kind of book from ‘Paper Magic’. ‘Secrets of Origami’ did contain some traditional designs, but the bulk of the book was devoted to explaining the new work of ten creative paperfolders, Robert Harbin himself, Florence Temko, Ligia Montoya, John M Nordquist, Jack J Skillman, Adolfo Cerceda, Neal Elias, Fred Rohm, Robert Neale and George Rhoads. ‘Secrets of Origami’ was also one of the first books to use the so-called Yoshizawa-Randlett notation system which standardised the symbols used in origami diagrams, to the development of which Harbin had also substantially contributed.

Other books

Harbin continued to write other books about paper folding until 1977. His later books only contain a few of his own designs. They are mainly characterised by the inclusion of work from some of the great designers of the period, notably Neal Elias and Patricia Crawford, and, in stark contrast, of designs sent to him by other, often previously unknown, paperfolders, some of whom were quite young children.

The most successful of these books was the paperback version of his ‘Teach Yourself Origami’, originally titled just ‘Origami: The Art of Japanese Paperfolding’ but now usually known as ‘Origami 1’. This, and its follow-up, ‘More Origami’, more usually known as ‘Origami 2’, sold copies in the hundreds of thousands, and were translated into many languages. Harbin is reported to have said that he made more money from the publication of his origami books than he ever had from magic.

TV appearances

Quite early on, in fact as long ago as 1955, Harbin’s hands had appeared, folding paper, as ‘Mr. Left and Mr. Right’, in a short segment of the BBC children’s programme ‘Jigsaw’, which was shown on Saturday evenings. ‘Mr. Left and Mr. Right’ first aired on 2nd January 1955 and ran for six bi-weekly shows.

He continued to appear on television, mostly as a magician, but occasionally as a paperfolder. In 1963 he appeared, folding paper, on the BBC programme ‘Top Score’, which alternated weeks with the more famous ‘Crackerjack’. Between 1968 and 1971 he appeared in thirty-two fifteen-minute-long episodes of a series made by Yorkshire Television, called, simply, ‘Origami’, in which he demonstrated how to fold objects such as birds, animals, and flowers. These programmes were accompanied by a series of articles published in ITV’s "Look-In" magazine. Harbin’s 1975 book ‘Have Fun with Origami’ was a collection of designs sent in by viewers and readers during the course of this series.

Illness and death

Robert Harbin became ill in 1977, shortly after finishing the diagrams for his final book, ‘Origami 4’, and died in January 1978. Having no siblings or children, he bequeathed the copyright in his books to the British Origami Society and thus made that fledgling society financially secure.

Books and Publications

- (Only the first publication of each title is listed.)

- ‘Paper Magic: The Art of Paper Folding’, Oldbourne, 1956

- ‘Paper Folding Fun’, Oldbourne, 1960

- ‘Party Lines’, Oldbourne, 1963

- ‘Secrets of Origami, Old and New: The Japanese Art of Paper-Folding’, Oldbourne, 1964

- ‘Teach Yourself Origami’, The English Universities Press, 1968 (republished as ‘Origami 1: The Art of Paper-Folding’ in 1969)

- ‘Origami 2: The Art of Paper-Folding’, Hodder, 1971

- ‘Origami 3: The Art of Paper-Folding’, Hodder, 1972

- ‘Origami: A Step by Step Guide’, Hamlyn, 1974

- ‘Have Fun with Origami’, Severn House, 1975

- ‘Origami 4: The Art of Paper-Folding’, Hodder, 1977

Sources / References

Sources for the information on this page can be found on the Robert Harbin page of the Public Paperfolding History Project.

The article was authored by David Mitchell.

Author`s note: My thanks are due to Edwin Corrie, Mick Guy, and Laura Rosenberg for assistance in gathering information for this article.

Images by the courtesy of Robin Macey.

Diagrams presented with the approval of the copyrights holder, the BOS. Many thanks to Michael Guy for his help.

Here are 10 models that were folded by our members in memoriam of Robert Harbin, View all models

Robert Harbin - Origamist and Magician - Thank You

Folded by: DermotH

Robert Harbin - Origamist and Magician - Thank You

Folded by: DermotH